Individual who provides medical treatments and health advice

A health professional, healthcare professional, or healthcare worker (sometimes abbreviated HCW)[1] is a provider of health care treatment and advice based on formal training and experience. The field includes those who work as a nurse, physician (such as family physician, internist, obstetrician, psychiatrist, radiologist, surgeon etc.), physician assistant, registered dietitian, veterinarian, veterinary technician, optometrist, pharmacist, pharmacy technician, medical assistant, physical therapist, occupational therapist, dentist, midwife, psychologist, audiologist, or healthcare scientist, or who perform services in allied health professions. Experts in public health and community health are also health professionals.

Fields

[edit]

NY College of Health Professions massage therapy class

NY College of Health Professions massage therapy class

US Navy doctors deliver a healthy baby

US Navy doctors deliver a healthy baby

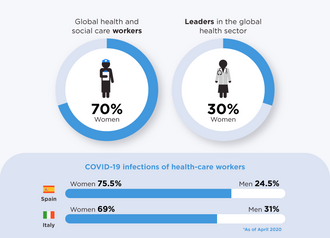

70% of global health and social care workers are women, 30% of leaders in the global health sector are women

70% of global health and social care workers are women, 30% of leaders in the global health sector are women

The healthcare workforce comprises a wide variety of professions and occupations who provide some type of healthcare service, including such direct care practitioners as physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, respiratory therapists, dentists, pharmacists, speech-language pathologist, physical therapists, occupational therapists, physical and behavior therapists, as well as allied health professionals such as phlebotomists, medical laboratory scientists, dieticians, and social workers. They often work in hospitals, healthcare centers and other service delivery points, but also in academic training, research, and administration. Some provide care and treatment services for patients in private homes. Many countries have a large number of community health workers who work outside formal healthcare institutions. Managers of healthcare services, health information technicians, and other assistive personnel and support workers are also considered a vital part of health care teams.[2]

Healthcare practitioners are commonly grouped into health professions. Within each field of expertise, practitioners are often classified according to skill level and skill specialization. "Health professionals" are highly skilled workers, in professions that usually require extensive knowledge including university-level study leading to the award of a first degree or higher qualification.[3] This category includes physicians, physician assistants, registered nurses, veterinarians, veterinary technicians, veterinary assistants, dentists, midwives, radiographers, pharmacists, physiotherapists, optometrists, operating department practitioners and others. Allied health professionals, also referred to as "health associate professionals" in the International Standard Classification of Occupations, support implementation of health care, treatment and referral plans usually established by medical, nursing, respiratory care, and other health professionals, and usually require formal qualifications to practice their profession. In addition, unlicensed assistive personnel assist with providing health care services as permitted.[citation needed]

Another way to categorize healthcare practitioners is according to the sub-field in which they practice, such as mental health care, pregnancy and childbirth care, surgical care, rehabilitation care, or public health.[citation needed]

Mental health

[edit]

Main article: Mental health professional

A mental health professional is a health worker who offers services to improve the mental health of individuals or treat mental illness. These include psychiatrists, psychiatry physician assistants, clinical, counseling, and school psychologists, occupational therapists, clinical social workers, psychiatric-mental health nurse practitioners, marriage and family therapists, mental health counselors, as well as other health professionals and allied health professions. These health care providers often deal with the same illnesses, disorders, conditions, and issues; however, their scope of practice often differs. The most significant difference across categories of mental health practitioners is education and training.[4] There are many damaging effects to the health care workers. Many have had diverse negative psychological symptoms ranging from emotional trauma to very severe anxiety. Health care workers have not been treated right and because of that their mental, physical, and emotional health has been affected by it. The SAGE author's said that there were 94% of nurses that had experienced at least one PTSD after the traumatic experience. Others have experienced nightmares, flashbacks, and short and long term emotional reactions.[5] The abuse is causing detrimental effects on these health care workers. Violence is causing health care workers to have a negative attitude toward work tasks and patients, and because of that they are "feeling pressured to accept the order, dispense a product, or administer a medication".[6] Sometimes it can range from verbal to sexual to physical harassment, whether the abuser is a patient, patient's families, physician, supervisors, or nurses.[citation needed]

Obstetrics

[edit]

Main articles: Obstetrics, Midwifery, and Birth attendant

A maternal and newborn health practitioner is a health care expert who deals with the care of women and their children before, during and after pregnancy and childbirth. Such health practitioners include obstetricians, physician assistants, midwives, obstetrical nurses and many others. One of the main differences between these professions is in the training and authority to provide surgical services and other life-saving interventions.[7] In some developing countries, traditional birth attendants, or traditional midwives, are the primary source of pregnancy and childbirth care for many women and families, although they are not certified or licensed. According to research, rates for unhappiness among obstetrician-gynecologists (Ob-Gyns) range somewhere between 40 and 75 percent.[8]

Geriatrics

[edit]

Main articles: Geriatrics and Geriatric care management

A geriatric care practitioner plans and coordinates the care of the elderly and/or disabled to promote their health, improve their quality of life, and maintain their independence for as long as possible.[9] They include geriatricians, occupational therapists, physician assistants, adult-gerontology nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, geriatric clinical pharmacists, geriatric nurses, geriatric care managers, geriatric aides, nursing aides, caregivers and others who focus on the health and psychological care needs of older adults.[citation needed]

Surgery

[edit]

A surgical practitioner is a healthcare professional and expert who specializes in the planning and delivery of a patient's perioperative care, including during the anaesthetic, surgical and recovery stages. They may include general and specialist surgeons, physician assistants, assistant surgeons, surgical assistants, veterinary surgeons, veterinary technicians. anesthesiologists, anesthesiologist assistants, nurse anesthetists, surgical nurses, clinical officers, operating department practitioners, anaesthetic technicians, perioperative nurses, surgical technologists, and others.[citation needed]

Rehabilitation

[edit]

A rehabilitation care practitioner is a health worker who provides care and treatment which aims to enhance and restore functional ability and quality of life to those with physical impairments or disabilities. These include physiatrists, physician assistants, rehabilitation nurses, clinical nurse specialists, nurse practitioners, physiotherapists, chiropractors, orthotists, prosthetists, occupational therapists, recreational therapists, audiologists, speech and language pathologists, respiratory therapists, rehabilitation counsellors, physical rehabilitation therapists, athletic trainers, physiotherapy technicians, orthotic technicians, prosthetic technicians, personal care assistants, and others.[10]

Optometry

[edit]

Main article: Optometry

Optometry is a field traditionally associated with the correction of refractive errors using glasses or contact lenses, and treating eye diseases. Optometrists also provide general eye care, including screening exams for glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy and management of routine or eye conditions. Optometrists may also undergo further training in order to specialize in various fields, including glaucoma, medical retina, low vision, or paediatrics. In some countries, such as the United Kingdom, United States, and Canada, Optometrists may also undergo further training in order to be able to perform some surgical procedures.

Diagnostics

[edit]

Main article: Medical diagnosis

Medical diagnosis providers are health workers responsible for the process of determining which disease or condition explains a person's symptoms and signs. It is most often referred to as diagnosis with the medical context being implicit. This usually involves a team of healthcare providers in various diagnostic units. These include radiographers, radiologists, Sonographers, medical laboratory scientists, pathologists, and related professionals.[citation needed]

Dentistry

[edit]

Dental assistant on the right supporting a dental operator on the left, during a procedure.

Dental assistant on the right supporting a dental operator on the left, during a procedure.

Main article: Dentistry

A dental care practitioner is a health worker and expert who provides care and treatment to promote and restore oral health. These include dentists and dental surgeons, dental assistants, dental auxiliaries, dental hygienists, dental nurses, dental technicians, dental therapists or oral health therapists, and related professionals.

Podiatry

[edit]

Care and treatment for the foot, ankle, and lower leg may be delivered by podiatrists, chiropodists, pedorthists, foot health practitioners, podiatric medical assistants, podiatric nurse and others.

Public health

[edit]

A public health practitioner focuses on improving health among individuals, families and communities through the prevention and treatment of diseases and injuries, surveillance of cases, and promotion of healthy behaviors. This category includes community and preventive medicine specialists, physician assistants, public health nurses, pharmacist, clinical nurse specialists, dietitians, environmental health officers (public health inspectors), paramedics, epidemiologists, public health dentists, and others.[citation needed]

Alternative medicine

[edit]

In many societies, practitioners of alternative medicine have contact with a significant number of people, either as integrated within or remaining outside the formal health care system. These include practitioners in acupuncture, Ayurveda, herbalism, homeopathy, naturopathy, Reiki, Shamballa Reiki energy healing Archived 2021-01-25 at the Wayback Machine, Siddha medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, traditional Korean medicine, Unani, and Yoga. In some countries such as Canada, chiropractors and osteopaths (not to be confused with doctors of osteopathic medicine in the United States) are considered alternative medicine practitioners.

Occupational hazards

[edit]

See also: Occupational hazards in dentistry and Nursing § Occupational hazards

A healthcare professional wears an air sampling device to investigate exposure to airborne influenza

A video describing the Occupational Health and Safety Network, a tool for monitoring occupational hazards to health care workers

A healthcare professional wears an air sampling device to investigate exposure to airborne influenza

A video describing the Occupational Health and Safety Network, a tool for monitoring occupational hazards to health care workers

The healthcare workforce faces unique health and safety challenges and is recognized by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) as a priority industry sector in the National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA) to identify and provide intervention strategies regarding occupational health and safety issues.[11]

Biological hazards

[edit]

Exposure to respiratory infectious diseases like tuberculosis (caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis) and influenza can be reduced with the use of respirators; this exposure is a significant occupational hazard for health care professionals.[12] Healthcare workers are also at risk for diseases that are contracted through extended contact with a patient, including scabies.[13] Health professionals are also at risk for contracting blood-borne diseases like hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS through needlestick injuries or contact with bodily fluids.[14][15] This risk can be mitigated with vaccination when there is a vaccine available, like with hepatitis B.[15] In epidemic situations, such as the 2014-2016 West African Ebola virus epidemic or the 2003 SARS outbreak, healthcare workers are at even greater risk, and were disproportionately affected in both the Ebola and SARS outbreaks.[16]

In general, appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) is the first-line mode of protection for healthcare workers from infectious diseases. For it to be effective against highly contagious diseases, personal protective equipment must be watertight and prevent the skin and mucous membranes from contacting infectious material. Different levels of personal protective equipment created to unique standards are used in situations where the risk of infection is different. Practices such as triple gloving and multiple respirators do not provide a higher level of protection and present a burden to the worker, who is additionally at increased risk of exposure when removing the PPE. Compliance with appropriate personal protective equipment rules may be difficult in certain situations, such as tropical environments or low-resource settings. A 2020 Cochrane systematic review found low-quality evidence that using more breathable fabric in PPE, double gloving, and active training reduce the risk of contamination but that more randomized controlled trials are needed for how best to train healthcare workers in proper PPE use.[16]

Tuberculosis screening, testing, and education

[edit]

Based on recommendations from The United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for TB screening and testing the following best practices should be followed when hiring and employing Health Care Personnel.[17]

When hiring Health Care Personnel, the applicant should complete the following:[18] a TB risk assessment,[19] a TB symptom evaluation for at least those listed on the Signs & Symptoms page,[20] a TB test in accordance with the guidelines for Testing for TB Infection,[21] and additional evaluation for TB disease as needed (e.g. chest x-ray for HCP with a positive TB test)[18] The CDC recommends either a blood test, also known as an interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA), or a skin test, also known as a Mantoux tuberculin skin test (TST).[21] A TB blood test for baseline testing does not require two-step testing. If the skin test method is used to test HCP upon hire, then two-step testing should be used. A one-step test is not recommended.[18]

The CDC has outlined further specifics on recommended testing for several scenarios.[22] In summary:

- Previous documented positive skin test (TST) then a further TST is not recommended

- Previous documented negative TST within 12 months before employment OR at least two documented negative TSTs ever then a single TST is recommended

- All other scenarios, with the exception of programs using blood tests, the recommended testing is a two-step TST

According to these recommended testing guidelines any two negative TST results within 12 months of each other constitute a two-step TST.

For annual screening, testing, and education, the only recurring requirement for all HCP is to receive TB education annually.[18] While the CDC offers education materials, there is not a well defined requirement as to what constitutes a satisfactory annual education. Annual TB testing is no longer recommended unless there is a known exposure or ongoing transmission at a healthcare facility. Should an HCP be considered at increased occupational risk for TB annual screening may be considered. For HCP with a documented history of a positive TB test result do not need to be re-tested but should instead complete a TB symptom evaluation. It is assumed that any HCP who has undergone a chest x-ray test has had a previous positive test result. When considering mental health you may see your doctor to be evaluated at your digression. It is recommended to see someone at least once a year in order to make sure that there has not been any sudden changes.[23]

Psychosocial hazards

[edit]

Occupational stress and occupational burnout are highly prevalent among health professionals.[24] Some studies suggest that workplace stress is pervasive in the health care industry because of inadequate staffing levels, long work hours, exposure to infectious diseases and hazardous substances leading to illness or death, and in some countries threat of malpractice litigation. Other stressors include the emotional labor of caring for ill people and high patient loads. The consequences of this stress can include substance abuse, suicide, major depressive disorder, and anxiety, all of which occur at higher rates in health professionals than the general working population. Elevated levels of stress are also linked to high rates of burnout, absenteeism and diagnostic errors, and reduced rates of patient satisfaction.[25] In Canada, a national report (Canada's Health Care Providers) also indicated higher rates of absenteeism due to illness or disability among health care workers compared to the rest of the working population, although those working in health care reported similar levels of good health and fewer reports of being injured at work.[26]

There is some evidence that cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation training and therapy (including meditation and massage), and modifying schedules can reduce stress and burnout among multiple sectors of health care providers. Research is ongoing in this area, especially with regards to physicians, whose occupational stress and burnout is less researched compared to other health professions.[27]

Healthcare workers are at higher risk of on-the-job injury due to violence. Drunk, confused, and hostile patients and visitors are a continual threat to providers attempting to treat patients. Frequently, assault and violence in a healthcare setting goes unreported and is wrongly assumed to be part of the job.[28] Violent incidents typically occur during one-on-one care; being alone with patients increases healthcare workers' risk of assault.[29] In the United States, healthcare workers experience

2⁄3 of nonfatal workplace violence incidents.[28] Psychiatric units represent the highest proportion of violent incidents, at 40%; they are followed by geriatric units (20%) and the emergency department (10%). Workplace violence can also cause psychological trauma.[29]

Health care professionals are also likely to experience sleep deprivation due to their jobs. Many health care professionals are on a shift work schedule, and therefore experience misalignment of their work schedule and their circadian rhythm. In 2007, 32% of healthcare workers were found to get fewer than 6 hours of sleep a night. Sleep deprivation also predisposes healthcare professionals to make mistakes that may potentially endanger a patient.[30]

COVID pandemic

[edit]

Especially in times like the present (2020), the hazards of health professional stem into the mental health. Research from the last few months highlights that COVID-19 has contributed greatly to the degradation of mental health in healthcare providers. This includes, but is not limited to, anxiety, depression/burnout, and insomnia.[citation needed]

A study done by Di Mattei et al. (2020) revealed that 12.63% of COVID nurses and 16.28% of other COVID healthcare workers reported extremely severe anxiety symptoms at the peak of the pandemic.[31] In addition, another study was conducted on 1,448 full time employees in Japan. The participants were surveyed at baseline in March 2020 and then again in May 2020. The result of the study showed that psychological distress and anxiety had increased more among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak.[32]

Similarly, studies have also shown that following the pandemic, at least one in five healthcare professionals report symptoms of anxiety.[33] Specifically, the aspect of "anxiety was assessed in 12 studies, with a pooled prevalence of 23.2%" following COVID.[33] When considering all 1,448 participants that percentage makes up about 335 people.

Abuse by patients

[edit]

- The patients are selecting victims who are more vulnerable. For example, Cho said that these would be the nurses that are lacking experience or trying to get used to their new roles at work.[34]

- Others authors that agree with this are Vento, Cainelli, & Vallone and they said that, the reason patients have caused danger to health care workers is because of insufficient communication between them, long waiting lines, and overcrowding in waiting areas.[35] When patients are intrusive and/or violent toward the faculty, this makes the staff question what they should do about taking care of a patient.

- There have been many incidents from patients that have really caused some health care workers to be traumatized and have so much self doubt. Goldblatt and other authors said that there was a lady who was giving birth, her husband said, "Who is in charge around here"? "Who are these sluts you employ here".[5] This was very avoidable to have been said to the people who are taking care of your wife and child.

Physical and chemical hazards

[edit]

Slips, trips, and falls are the second-most common cause of worker's compensation claims in the US and cause 21% of work absences due to injury. These injuries most commonly result in strains and sprains; women, those older than 45, and those who have been working less than a year in a healthcare setting are at the highest risk.[36]

An epidemiological study published in 2018 examined the hearing status of noise-exposed health care and social assistance (HSA) workers sector to estimate and compare the prevalence of hearing loss by subsector within the sector. Most of the HSA subsector prevalence estimates ranged from 14% to 18%, but the Medical and Diagnostic Laboratories subsector had 31% prevalence and the Offices of All Other Miscellaneous Health Practitioners had a 24% prevalence. The Child Day Care Services subsector also had a 52% higher risk than the reference industry.[37]

Exposure to hazardous drugs, including those for chemotherapy, is another potential occupational risk. These drugs can cause cancer and other health conditions.[38]

Gender factors

[edit]

Female health care workers may face specific types of workplace-related health conditions and stress. According to the World Health Organization, women predominate in the formal health workforce in many countries and are prone to musculoskeletal injury (caused by physically demanding job tasks such as lifting and moving patients) and burnout. Female health workers are exposed to hazardous drugs and chemicals in the workplace which may cause adverse reproductive outcomes such as spontaneous abortion and congenital malformations. In some contexts, female health workers are also subject to gender-based violence from coworkers and patients.[39][40]

Workforce shortages

[edit]

See also: Health workforce, Doctor shortage, and Nursing shortage

Many jurisdictions report shortfalls in the number of trained health human resources to meet population health needs and/or service delivery targets, especially in medically underserved areas. For example, in the United States, the 2010 federal budget invested $330 million to increase the number of physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses, and dentists practicing in areas of the country experiencing shortages of trained health professionals. The Budget expands loan repayment programs for physicians, nurses, and dentists who agree to practice in medically underserved areas. This funding will enhance the capacity of nursing schools to increase the number of nurses. It will also allow states to increase access to oral health care through dental workforce development grants. The Budget's new resources will sustain the expansion of the health care workforce funded in the Recovery Act.[41] There were 15.7 million health care professionals in the US as of 2011.[36]

In Canada, the 2011 federal budget announced a Canada Student Loan forgiveness program to encourage and support new family physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and nurses to practice in underserved rural or remote communities of the country, including communities that provide health services to First Nations and Inuit populations.[42]

In Uganda, the Ministry of Health reports that as many as 50% of staffing positions for health workers in rural and underserved areas remain vacant. As of early 2011, the Ministry was conducting research and costing analyses to determine the most appropriate attraction and retention packages for medical officers, nursing officers, pharmacists, and laboratory technicians in the country's rural areas.[43]

At the international level, the World Health Organization estimates a shortage of almost 4.3 million doctors, midwives, nurses, and support workers worldwide to meet target coverage levels of essential primary health care interventions.[44] The shortage is reported most severe in 57 of the poorest countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

Nurses are the most common type of medical field worker to face shortages around the world. There are numerous reasons that the nursing shortage occurs globally. Some include: inadequate pay, a large percentage of working nurses are over the age of 45 and are nearing retirement age, burnout, and lack of recognition.[45]

Incentive programs have been put in place to aid in the deficit of pharmacists and pharmacy students. The reason for the shortage of pharmacy students is unknown but one can infer that it is due to the level of difficulty in the program.[46]

Results of nursing staff shortages can cause unsafe staffing levels that lead to poor patient care. Five or more incidents that occur per day in a hospital setting as a result of nurses who do not receive adequate rest or meal breaks is a common issue.[47]

Regulation and registration

[edit]

Main article: Health professional requisites

Practicing without a license that is valid and current is typically illegal. In most jurisdictions, the provision of health care services is regulated by the government. Individuals found to be providing medical, nursing or other professional services without the appropriate certification or license may face sanctions and criminal charges leading to a prison term. The number of professions subject to regulation, requisites for individuals to receive professional licensure, and nature of sanctions that can be imposed for failure to comply vary across jurisdictions.

In the United States, under Michigan state laws, an individual is guilty of a felony if identified as practicing in the health profession without a valid personal license or registration. Health professionals can also be imprisoned if found guilty of practicing beyond the limits allowed by their licenses and registration. The state laws define the scope of practice for medicine, nursing, and a number of allied health professions.[48][unreliable source?] In Florida, practicing medicine without the appropriate license is a crime classified as a third degree felony,[49] which may give imprisonment up to five years. Practicing a health care profession without a license which results in serious bodily injury classifies as a second degree felony,[49] providing up to 15 years' imprisonment.

In the United Kingdom, healthcare professionals are regulated by the state; the UK Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) protects the 'title' of each profession it regulates. For example, it is illegal for someone to call himself an Occupational Therapist or Radiographer if they are not on the register held by the HCPC.

See also

[edit]

- List of healthcare occupations

- Community health center

- Chronic care management

- Electronic superbill

- Geriatric care management

- Health human resources

- Uniform Emergency Volunteer Health Practitioners Act

References

[edit]

- ^

"HCWs With Long COVID Report Doubt, Disbelief From Colleagues". Medscape. 29 November 2021.

- ^ World Health Organization, 2006. World Health Report 2006: working together for health. Geneva: WHO.

- ^ "Classifying health workers" (PDF). World Health Organization. Geneva. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-08-16. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- ^ "Difference Between Psychologists and Psychiatrists". Psychology.about.com. 2007. Archived from the original on April 3, 2007. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

- ^ a b Goldblatt, Hadass; Freund, Anat; Drach-Zahavy, Anat; Enosh, Guy; Peterfreund, Ilana; Edlis, Neomi (2020-05-01). "Providing Health Care in the Shadow of Violence: Does Emotion Regulation Vary Among Hospital Workers From Different Professions?". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 35 (9–10): 1908–1933. doi:10.1177/0886260517700620. ISSN 0886-2605. PMID 29294693. S2CID 19304885.

- ^ Johnson, Cheryl L.; DeMass Martin, Suzanne L.; Markle-Elder, Sara (April 2007). "Stopping Verbal Abuse in the Workplace". American Journal of Nursing. 107 (4): 32–34. doi:10.1097/01.naj.0000271177.59574.c5. ISSN 0002-936X. PMID 17413727.

- ^ Gupta N et al. "Human resources for maternal, newborn and child health: from measurement and planning to performance for improved health outcomes. Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine Human Resources for Health, 2011, 9(16). Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "Ob-Gyn Burnout: Why So Many Doctors Are Questioning Their Calling". healthecareers.com. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ Araujo de Carvalho, Islene; Epping-Jordan, JoAnne; Pot, Anne Margriet; Kelley, Edward; Toro, Nuria; Thiyagarajan, Jotheeswaran A; Beard, John R (2017-11-01). "Organizing integrated health-care services to meet older people's needs". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 95 (11): 756–763. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.187617 (inactive 5 December 2024). ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 5677611. PMID 29147056.

cite journal: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link)

- ^ Gupta N et al. "Health-related rehabilitation services: assessing the global supply of and need for human resources." Archived 2012-07-20 at the Wayback Machine BMC Health Services Research, 2011, 11:276. Published 17 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "National Occupational Research Agenda for Healthcare and Social Assistance | NIOSH | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-02-15. Retrieved 2019-03-14.

- ^ Bergman, Michael; Zhuang, Ziqing; Shaffer, Ronald E. (25 July 2013). "Advanced Headforms for Evaluating Respirator Fit". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ FitzGerald, Deirdre; Grainger, Rachel J.; Reid, Alex (2014). "Interventions for preventing the spread of infestation in close contacts of people with scabies". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (2): CD009943. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009943.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 10819104. PMID 24566946.

- ^ Cunningham, Thomas; Burnett, Garrett (17 May 2013). "Does your workplace culture help protect you from hepatitis?". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ a b Reddy, Viraj K; Lavoie, Marie-Claude; Verbeek, Jos H; Pahwa, Manisha (14 November 2017). "Devices for preventing percutaneous exposure injuries caused by needles in healthcare personnel". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (11): CD009740. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009740.pub3. PMC 6491125. PMID 29190036.

- ^ a b Verbeek, Jos H.; Rajamaki, Blair; Ijaz, Sharea; Sauni, Riitta; Toomey, Elaine; Blackwood, Bronagh; Tikka, Christina; Ruotsalainen, Jani H.; Kilinc Balci, F. Selcen (May 15, 2020). "Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (5): CD011621. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011621.pub5. hdl:1983/b7069408-3bf6-457a-9c6f-ecc38c00ee48. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8785899. PMID 32412096. S2CID 218649177.

- ^ Sosa, Lynn E. (April 2, 2019). "Tuberculosis Screening, Testing, and Treatment of U.S. Health Care Personnel: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2019". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (19): 439–443. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6819a3. PMC 6522077. PMID 31099768.

- ^ a b c d "Testing Health Care Workers | Testing & Diagnosis | TB | CDC". www.cdc.gov. March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Health Care Personnel (HCP) Baseline Individual TB Risk Assessment" (PDF). cdc.gov. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "Signs & Symptoms | Basic TB Facts | TB | CDC". www.cdc.gov. February 4, 2021.

- ^ a b "Testing for TB Infection | Testing & Diagnosis | TB | CDC". www.cdc.gov. March 8, 2021.

- ^ "Guidelines for Preventing the Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Health-Care Settings, 2005". www.cdc.gov.

- ^ Spoorthy, Mamidipalli Sai; Pratapa, Sree Karthik; Mahant, Supriya (June 2020). "Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic–A review". Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 51: 102119. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102119. PMC 7175897. PMID 32339895.

- ^ Ruotsalainen, Jani H.; Verbeek, Jos H.; Mariné, Albert; Serra, Consol (2015-04-07). "Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (4): CD002892. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002892.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6718215. PMID 25847433.

- ^ "Exposure to Stress: Occupational Hazards in Hospitals". NIOSH Publication No. 2008–136 (July 2008). 2 December 2008. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB2008136. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008.

- ^ Canada's Health Care Providers, 2007 (Report). Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

- ^ Ruotsalainen, JH; Verbeek, JH; Mariné, A; Serra, C (7 April 2015). "Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (4): CD002892. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002892.pub5. PMC 6718215. PMID 25847433.

- ^ a b Hartley, Dan; Ridenour, Marilyn (12 August 2013). "Free On-line Violence Prevention Training for Nurses". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 16 January 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ a b Hartley, Dan; Ridenour, Marilyn (September 13, 2011). "Workplace Violence in the Healthcare Setting". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH. Archived from the original on February 8, 2014.

- ^ Caruso, Claire C. (August 2, 2012). "Running on Empty: Fatigue and Healthcare Professionals". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013.

- ^ Di Mattei, Valentina; Perego, Gaia; Milano, Francesca; Mazzetti, Martina; Taranto, Paola; Di Pierro, Rossella; De Panfilis, Chiara; Madeddu, Fabio; Preti, Emanuele (2021-05-15). "The "Healthcare Workers' Wellbeing (Benessere Operatori)" Project: A Picture of the Mental Health Conditions of Italian Healthcare Workers during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18 (10): 5267. doi:10.3390/ijerph18105267. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 8156728. PMID 34063421.

- ^ Sasaki, Natsu; Kuroda, Reiko; Tsuno, Kanami; Kawakami, Norito (2020-11-01). "The deterioration of mental health among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak: A population-based cohort study of workers in Japan". Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 46 (6): 639–644. doi:10.5271/sjweh.3922. ISSN 0355-3140. PMC 7737801. PMID 32905601.

- ^ a b Pappa, Sofia; Ntella, Vasiliki; Giannakas, Timoleon; Giannakoulis, Vassilis G.; Papoutsi, Eleni; Katsaounou, Paraskevi (August 2020). "Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 88: 901–907. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. PMC 7206431. PMID 32437915.

- ^ Cho, Hyeonmi; Pavek, Katie; Steege, Linsey (2020-07-22). "Workplace verbal abuse, nurse-reported quality of care and patient safety outcomes among early-career hospital nurses". Journal of Nursing Management. 28 (6): 1250–1258. doi:10.1111/jonm.13071. ISSN 0966-0429. PMID 32564407. S2CID 219972442.

- ^ Vento, Sandro; Cainelli, Francesca; Vallone, Alfredo (2020-09-18). "Violence Against Healthcare Workers: A Worldwide Phenomenon With Serious Consequences". Frontiers in Public Health. 8: 570459. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.570459. ISSN 2296-2565. PMC 7531183. PMID 33072706.

- ^ a b Collins, James W.; Bell, Jennifer L. (June 11, 2012). "Slipping, Tripping, and Falling at Work". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012.

- ^ Masterson, Elizabeth A.; Themann, Christa L.; Calvert, Geoffrey M. (2018-04-15). "Prevalence of Hearing Loss Among Noise-Exposed Workers Within the Health Care and Social Assistance Sector, 2003 to 2012". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 60 (4): 350–356. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001214. ISSN 1076-2752. PMID 29111986. S2CID 4637417.

- ^ Connor, Thomas H. (March 7, 2011). "Hazardous Drugs in Healthcare". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012.

- ^ World Health Organization. Women and health: today's evidence, tomorrow's agenda. Archived 2012-12-25 at the Wayback Machine Geneva, 2009. Retrieved on March 9, 2011.

- ^ Swanson, Naomi; Tisdale-Pardi, Julie; MacDonald, Leslie; Tiesman, Hope M. (13 May 2013). "Women's Health at Work". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved 2009-03-06 – via National Archives.

- ^ Government of Canada. 2011. Canada's Economic Action Plan: Forgiving Loans for New Doctors and Nurses in Under-Served Rural and Remote Areas. Ottawa, 22 March 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Rockers P et al. Determining Priority Retention Packages to Attract and Retain Health Workers in Rural and Remote Areas in Uganda. Archived 2011-05-23 at the Wayback Machine CapacityPlus Project. February 2011.

- ^ "The World Health Report 2006 - Working together for health". Geneva: WHO: World Health Organization. 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-02-28.

- ^ Mefoh, Philip Chukwuemeka; Ude, Eze Nsi; Chukwuorji, JohBosco Chika (2019-01-02). "Age and burnout syndrome in nursing professionals: moderating role of emotion-focused coping". Psychology, Health & Medicine. 24 (1): 101–107. doi:10.1080/13548506.2018.1502457. ISSN 1354-8506. PMID 30095287. S2CID 51954488.

- ^ Traynor, Kate (2003-09-15). "Staffing shortages plague nation's pharmacy schools". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 60 (18): 1822–1824. doi:10.1093/ajhp/60.18.1822. ISSN 1079-2082. PMID 14521029.

- ^ Leslie, G. D. (October 2008). "Critical Staffing shortage". Australian Nursing Journal. 16 (4): 16–17. doi:10.1016/s1036-7314(05)80033-5. ISSN 1036-7314. PMID 14692155.

- ^ wiki.bmezine.com --> Practicing Medicine. In turn citing Michigan laws

- ^ a b CHAPTER 2004-256 Committee Substitute for Senate Bill No. 1118 Archived 2011-07-23 at the Wayback Machine State of Florida, Department of State.

External links

[edit]

- World Health Organization: Health workers

Health care

| |

- Economics

- Equipment

- Guidelines

- Industry

- Philosophy

- Policy

- Providers

- Public health

- Ranking

- Reform

- System

|

| Professions |

- Medicine

- Nursing

- Pharmacy

- Healthcare science

- Dentistry

- Allied health professions

- Health information management

|

| Settings |

- Assisted living

- Clinic

- Hospital

- Nursing home

- Medical school (Academic health science centre, Teaching hospital)

- Pharmacy school

- Supervised injection site

|

| Care |

- Acute

- Chronic

- End-of-life

- Hospice

- Overutilization

- Palliative

- Primary

- Self

- Total

|

| Skills / training |

- Bedside manner

- Cultural competence

- Diagnosis

- Education

- Universal precautions

|

| Technology |

- 3D bioprinting

- Artificial intelligence

- Connected health

- Digital health

- Electronic health records

- mHealth

- Nanomedicine

- Telemedicine

|

| Health informatics |

- Medical image computing and imaging informatics

- Artificial intelligence in healthcare

- Neuroinformatics in healthcare

- Behavior informatics in healthcare

- Computational biology in healthcare

- Translational bioinformatics

- Translational medicine

- health information technology

- Telemedicine

- Public health informatics

- Health information management

- Consumer health informatics

|

| By country |

- United States

- reform debate in the United States

- History of public health in the United States

- United Kingdom

- Canada

- Australia

- New Zealand

- (Category Health care by country)

|

Category Category

|

Authority control databases: National  |

|